Preface

If the content here seems to be out of context, you’ll probably want to start from here.

So, you have got your tools in your bag from the Docs, Commands and Tools post and you have already made the most exciting program, a blinky, working on your PRUs with the help of this blinky. Exciting ! Isnt it ? Okay so lets move furthe. In the blinky I tried to explain the working of deploy.sh script and the AM335x_PRU.cmd file. And promised to explain the working of Makefile and resource_table.h file in the future posts. So here this is post is going to keep that promise, with a bit of twist. I will explain the working of Makefile wewe and resource_table.h wewe file, but using the pru_inline_assembli example wewe.

Content

PRU inline assembly example

In this wewe post, I explained the significance and usage of PRUs. I would summarize it by saying that PRUs are used for realtime applications where timing is very very crucial. This may include bitbanging to emulate a particular bus protocol this project wewe, to take fast data like the beaglescope wewe project does. C/C++ provides really nice interface for a very good number of tasks. But when very tight timing constraints are posed on the system, Assembly language is used. Though it is somewhat tricky and bit of exhaustive to use assembly, it allows the developer to tweak the parts of code that have to very precise about timings.

Picture credits : MarkTraceur and imgur

The pru inline example wewe does a very simple but interesting task … you probably guessed it correct, a blinky. There will be more posts in future to explain the constraints and the variations in the way of using Assembly, but this post, focuses on there starting steps the how to use inline assembly, the Makefile and resource_table.h file wewe.

-

I am Assuming that you already have cloned the BeagleScope repository form https://github.com/ZeekHuge/BeagleScope and that you keep it up to date, by pulling the latest contents. Also that you already have the setup that we did in blinky and the 2nd ptp post wewe.

-

Connect an LED ( and mind the value of the resistor you are using ) to one of the header pins connected to PRU1. Now using config-pin utility, set the pin in pruout mode. If you dont know how to use the config-pin utility, please refer this post wewe. So for example, you are using pin P8_45

$ config-pin P8_45 pruout 0_p

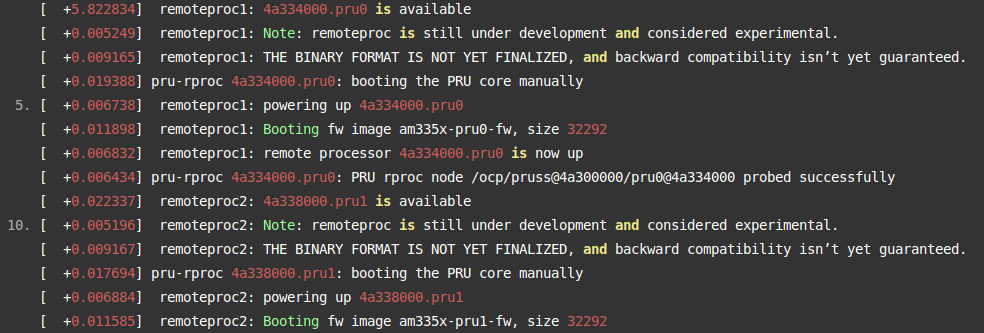

- Get into the ‘BeagleScope/examples/firmware_exmples/PRU_inline_asm_blinky/’ directory and simply execute the ‘make install’ command.

make install O_P

- Taadaa ! you have a blinky … ahh … again !.

Understanding inline assembly example code

- The main source code for PRU1 in this example is split into 2 parts. The main_pru1.c and the pru1-asm-blinky.asm.

-

main_pru1.c* - The main source file. The file contains a main() function, that gets invoked whenever the source code is loaded onto the PRU. The main function then calls the start(). We now discuss about the internals

- The extern keyword, is basically a ‘C’ keyword. But the compiler for PRUs support its use. Using extern keyword, indicates to the compiler that the symbol, that is, function or variable, is just declared in the source, and not defined. No memory is associated with such a symbol. What the compiler does is, it just creates a symbol for the start() function and leaves the task of combining it with its definition later, to the PRU linker.

-

pru1-asm-blinky.asm - This .asm file is the assemble source that actually defines the start(). As already told, the compilers do not worry about the definition of a fucntion. They worry just about its declaration. The assembly source file defines this function The PRU compiler can compile a ‘C’ file as well as it can act like an assembler and take an assembly source code as input. It further converts these files into ‘.object’ files.

-